An Israeli photojournalist puts Palestinians on Facebook

Five years ago, an invitation to a Palestinian wedding unleashed a chain of events for esteemed photographer Miki Kratsman that he could never have predicted. In 2011, he rolled up to the densely populated Jenin refugee camp, to celebrate the marriage of a friend’s son. Armed with 200 carefully selected photographs ─ taken throughout the West Bank and Gaza during a decades-long career as a photojournalist with Hadeshot and Ha’aretz ─ Kratsman wanted to identify people in his images.

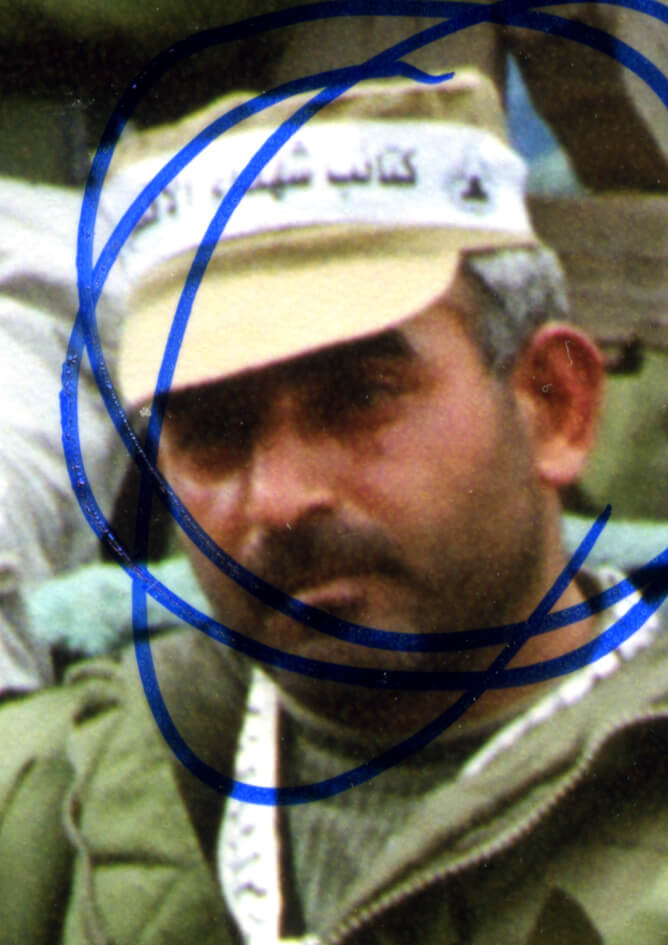

The uncommon scenario of an Israeli Jew attending a wedding in a Palestinian refugee camp meant Kratsman was accepted by locals immediately. He quickly found himself the centre of attention as people clamoured to spot themselves in his photos. As the Palestinians pored over the images taken during a 2007 parade of militia, he handed out pens and they circled the faces of those they knew were dead.

Returning home with 20 martyrs identified and keen to locate more Palestinians in his archive, Kratsman soon realised he couldn’t carry thousands of images all over the West Bank and Gaza. Then, prompted by his wife, he quickly understood the potential Facebook had to help in his quest.

“It was my wife’s idea and I said OK, it looks like I am going to be on Facebook,” he laughed.

People I Met

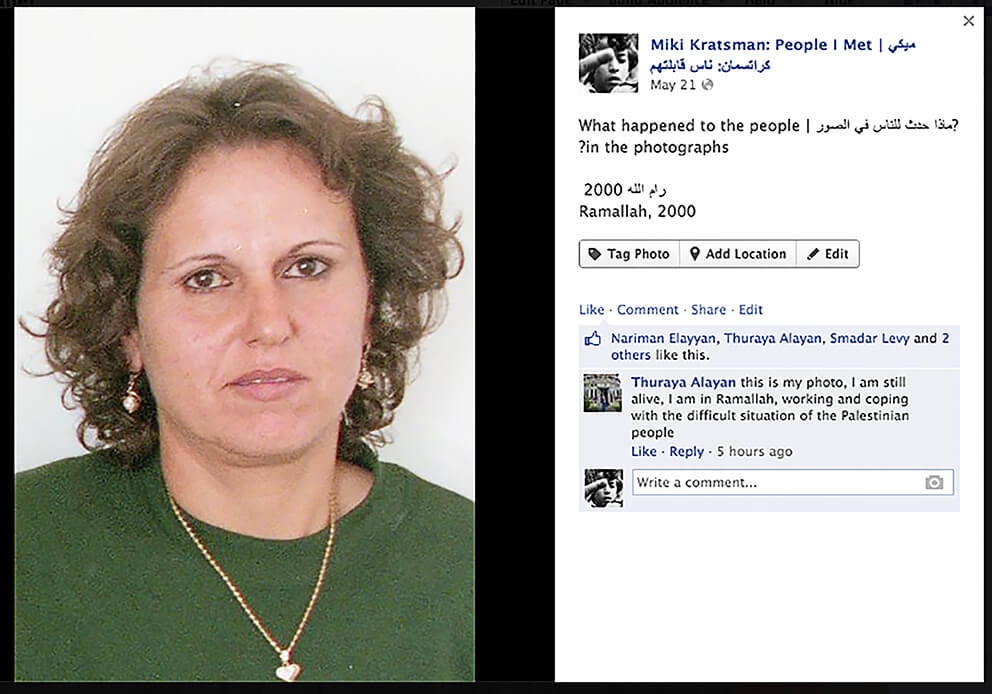

A Palestinian woman is identified as alive and well in a screenshot from the People I met Facebook page. (Image M.Kratsman)

The veteran photojournalist has documented the effects of Israel’s brutal occupation on Palestinian life for over three decades. Months into the second intifada, he realised he wanted to understand and portray the “unbelievable and impossible” conditions of Palestinian life.

“The catastrophe is the daily life for Palestinians, not a specific event,” he said.

While Israel’s chokehold dehumanises the Palestinians, Kratsman’s work attempts the opposite and evokes a sense of humanity. His personal message of opposition to the occupation of another people has not only stood the test of time, but evolves daily.

The faces of the deceased are circled in Kratsman’s images from Jenin refugee camp in 2007. (Image: M.Kratsman)

Since 2011, he has uploaded over 6000 facial portraits to his People I Met Facebook page. Captured over decades all over Gaza and the West Bank, the low resolution, low quality images, now adopt a fierce poignancy against the slick social media backdrop.

Urban and rural, young and old, male and female, with portraits of grinning children with missing front teeth belying their surrounding chaos, many adults share haunted expressions of anguish and determination.

Isolated from their original frame and context, the faces are uploaded with just the date, location and Kratsman’s simple question: “What happened to the people in the photographs?”

Seeing the possibilities sharing digital images had for opening up lines of communication, for the award-winning photographer People I Met was about creating a new form of archive. More importantly, it was about face recognition and bringing those on the periphery to the centre stage. “It’s not about art or good photos, it’s just about faces,” he explained.

“It’s to put the guy who is in the background most of the time, in the foreground. You’re someone at the side of the event, and suddenly you become ‘the one’. It’s also to think about all those faces I met at demonstrations and isolate them one by one. I really like the idea that they all became equal,” he added.

“It was also to write, together with the Palestinians, the history of each one of them.”

All kinds of stories

A Palestinian woman is identified as alive and well in a screenshot from the People I met Facebook page. (Image M.Kratsman)

Conscious that people may not want some of the circumstances the photographs were captured in to be published openly, Kratsman’s technique of isolating the faces, means they are absolutely out of context. “Context can be really bad for them,” he said.

Accumulating over 13,000 followers in five years, People I Met has seen a 40% increase in page engagement in the last year and Kratsman believes he knows why: “The Palestinians are addicted to Facebook!” he laughed.

While his page receives a steady flow of private messages, not all of them positive, on the whole people seem grateful, according to Kratsman. Many request photos of a specific time and place, while others want to see the complete frames and not just the cropped faces.

The faces of the deceased are circled in Kratsman’s images from Jenin refugee camp in 2007. (Image: M.Kratsman)

Responses to People I Met have been varied and range from the predictably tragic to the reassuring. Others are comical as Palestinians in the portraits are identified as celebrities, soccer players and even a young Michelle Obama.

Kratsman summed up the responses so far: “There are successful people with businesses, engineers, academics and those with big families. Some opened restaurants or became taxi drivers. All kinds of stories,” he said.

“Sadly, there are a lot of martyrs,” he continued. From those identified so far, seventy of the Palestinians are dead.

“There are very sad stories, like the 23-yr-old from Jenin refugee camp. On the same day I uploaded his photo, he was killed by the Israeli army, in an armed confrontation,” he sighed.

When the portraits are identified, Kratsman simply asks: “Is she/he in good health?”

He explained his brevity: “You know, it is very problematic as an Israeli to ask a lot of questions. I don’t want to be suspected as someone who’s trying to get information, so I just ask the same question. If they give more data that’s fine, but all I want to know is are they OK?”

Many Voices

Kratsman’s relationships with Palestinian friends go back decades and it has always been important for him to not just take photos and leave. Described as a leading chronicler of life in the occupied territories and a political artist and activist, the Argentinian-born grandfather moved to Israel in 1971.

For three decades he covered the West Bank and Gaza as a photojournalist for Israeli newspapers Hadashot and Ha’aretz. Also an archive worker, he has a distinguished career teaching at Israel’s leading art schools and his photography has been exhibited all over the world.

The faces of the deceased are circled in Kratsman’s images from Jenin refugee camp in 2007. (Image: M.Kratsman)

Other strings to his bow include the co-founding of Breaking the Silence where he now serves as Chairman of the board. In 2011, he was awarded Israel’s Emet Prize for Science, Arts and Culture and Harvard University’s Robert Gardner Fellowship in Photography.

Asked if he thinks his work has shaped Israeli public discourse, he was less than hopeful. Growing up with questions about the Vietnam War and the effect of photojournalism on public opinion, he recalled mournfully that it was back during the first intifada, when he once believed photojournalism could influence events in Palestine and Israel.

“Unfortunately it didn’t happen,” he sighed. “I listen to the news, I see the result of the last election and it looks like your question is irrelevant,” he said.

Adding: “What you do is not necessarily to have influence. You do some things because you can’t not do them. It’s not a decision.”

Today, Kratsman is upbeat about the increasing number of Palestinians documenting their own struggle. Recalling the first intifada when there were no Palestinian photographers, he said photos would appear in the press — claimed by AP and Reuters, but obviously taken by Palestinians — who were never named or credited.

“It’s very important that Palestinians are the ones who show what happens there because they have their own voice. On the other hand, it’s also important for an Israeli Jew to show his people what is happening at the same time. It’s a collaboration between us,” he said, adding:

“There are many voices, not just the voice of the perpetrator and the guy with the power.”

Miki Kratsman will be at Harvard University’s, Peabody Museum for a lecture, panel discussion and to sign his new book The Resolution of the Suspect on May 3rd. The International Center of Photography in New York is also hosting an evening with Miki on May 9th.